Background

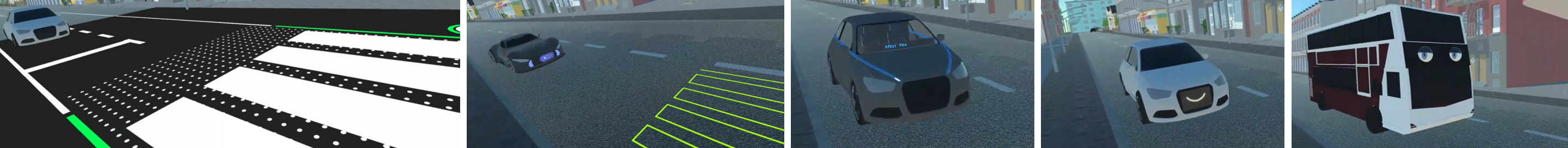

Social cues play an essential role in resolving road situations between car drivers and vulnerable road users (VRUs). However, this interaction might be more challenging in the presence of automated vehicles (AVs) [13]. Previous works focused on addressing this issue using external Human-Machine Interfaces (eHMIs, see Figure above) [7, 22] or by simulating social interactions via eye contact or gestures [36]. Such approaches primarily focus on visual stimuli (e.g., [16, 30]) and do not comply with Universal Design principles (see [9]), which excludes people with visual limitations [7]. In general, several groups, such as children, blind people, or older adults, are underrepresented in empirical evaluations of eHMI concepts for interaction between AVs and VRUs. We aim to develop inclusive solutions with the help of this workshop to make the traffic accessible for them. Moreover, these groups are not limited to the example groups discussed below and may also include people with hearing loss, wheelchair users, or skateboarders.

Children between six and thirteen are the most vulnerable subgroup among cyclists, due to the still-developing motor and perceptual-motor skills [1, 12]. Previous work tried to address the safety issue for child cyclists by augmenting bicycles and helmets to represent warnings [25], navigation [27], and lanekeeping cues [26]. Still, Deb et al. [10] identified children as underrepresented participants in studies with eHMIs. They revealed different behavior compared to the adult counterparts and identified a more risky behavior among children. Thus, we find it particularly important to explore the design space for children as VRUs like cyclists or pedestrians.

About 1.98 billion people are children (age 0 - 14) [28]. Road traffic injuries are the primary cause of death for children and adults aged 5-29 years [37].

Another group of underrepresented VRUs is people with visual limitations. Colley et al. [7] showed that current concepts mostly focus on visual stimuli. Design spaces in external communication of AVs [5, 24] acknowledge that other stimuli are feasible, but previous research did not adequately address them. Colley et al. also discussed existing auditory concepts with experts on accessibility [6]: recent concepts were rated as unusable. Thus, they introduced the “omniscient narrator”, an approach where one AV communicates for all relevant AVs.

About 1.3 billion people have some, and 217 million people moderate to severe, vision impairments. 36 million people are blind [4, 31]. 466 million people have disabling hearing loss [32].

Older adults are an important group of traffic participants. The world’s population of age 65 and above has been increasing and is projected to continue doing so [14, 34]. Thus, HumanComputer Interaction (HCI) research increasingly takes into account the additional user needs that come with aging [15]. For example, Dickinson et al. [11] provide an overview of methods for HCI research with older people. It has been shown that age plays a vital role in making crossing decisions [33]. Also, older adults seem to have different expectations for automated driving than younger adults [23]. It has also been shown that older adults take longer to adapt to new technology [2] and have different requirements [21].

The number of older adults is projected to increase with “persons over age 65 being the fastest-growing age group” [29]. By 2050, one in six persons is projected to be aged 65 or over [29].